Vitold Shmulian and Other Russian mathematicians on the Front Lines of WWII Helped Make It So. (VE Day 75th anniversary tribute)

Moscow Victory Parade of 1945. A Soviet stamp of 1946 with a slogan: Artillery in Victory Parade.

A soviet stamp of 1947 with a slogan: Artillery is the God of War.

During the difficult times of the Great Patriotic War, many Soviet scientists and mathematicians joined the army. One of them, Vitold Shmulian was a post-doctoral student at the prestigious Steklov Institute of Mathematics in Moscow. A few days after the Axis invasion of the Soviet Union began on June 22, 1941, he joined a group of co-workers in volunteering for the People’s Army (Narodnoe Opolchenie), which was soon reformed as the regular army. By November, Shmulian was an officer and had assumed the position of commander of a topographical reconnaissance team of an artillery regiment. He excelled in carrying out his military duties, and, based on his knowledge of mathematics, in particular, of the theory of probabilities, Shmulian introduced many improvements in the operation of the artillery units. This resulted in improved precision throughout the regiment and higher density-barrages on targets, always a desirable outcome for artillery on the battlefield.

Like Shmulian, several other Soviet mathematicians found themselves on the front lines during World War II and offered their mathematical skills to the military service. To name just a few, there were Alexey Lyapunov (1911-1973), who later became a leading expert in cybernetics in the USSR, and a future academician Yuri V. Linnik (1915-1972), who served with an artillery battery at the strategic Pulkovo Heights near Leningrad. What was unprecedented in the case of Vitold Shmulian was that despite the burdens of war and his duties as a commanding officer, which he carried out successfully and heroically, he found the strength to continue his academic research. This was aligned with the subject of the topology of the linear spaces, a field that came to prominence through the book of a renowned Polish mathematician Stefan Banach (1892-1945)1 [1] that was published in the early 1930s. Thereafter, from the trenches, he was able to send his mathematical treatises to the USSR Academy of Sciences. With the support of his colleagues, and particular, academician Andrey N. Kolmogorov, the preeminent mathematician of the 20th century (who also developed his own probabilistic methods and tables for the improvement of artillery shooting density), one of Shmulian’s works was published in the summer of 1944 and another after the war.

In modern times, only one other case of such a scientific feat achieved by an officer while under battlefield conditions is known. This is the case of Karl Schwarzschild (1873-1916), a physicist and member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences, who voluntarily served in the German army during World War I. In 1915, while serving as a lieutenant in the artillery on the Eastern Front, he provided the first exact solution to the Einstein field equations of general relativity [2].

Vitold Shmulian was born in 1914 in Kherson, Ukraine, a town on the Black Sea at the mouth of the Dnieper River (currently, an important port and center of shipbuilding activity). His father, Lev, was an attorney, and his mother, Isabella, also received a law degree but did not work much outside the house. Vitold had two siblings. His brother Theodor was two years older. His younger sister, Alla, was born in 1920. Vitold had a cultured family upbringing; his mother was the daughter of a well-to-do lawyer, who played a prominent role in the local chapter of the Kadet (Constitutional Democratic) Party as an elector in the State Duma (parliament). His mother was also a freelance poet and writer who converted various Russian fairy tales and plays into musicals.

The student years of Vitold coincided with the restoration of the Odessa State University. His former mathematics professor M.G. Krein wrote [3, 4] that when he met Vitold Shmulian in 1934, he was already the strongest student in his department. During the 1936–37 school year, Professor Krein began a lecture course and seminar around topics regarding Banach spaces, this important mathematical concept had been first described by noted Polish mathematician Stefan Banach and his colleagues in the 1920s. According to Krein, one of the most active participants of that seminar was Shmulian. He devised a number of elegant solutions in that area that continue to be studied and generalized by mathematicians today. During the very short time from 1937 to 1941, Shmulian published nearly twenty papers. Even at the front, Shmulian did not stop his studies, which he presented in the form of papers and letters sent to the Steklov Institute. A portion of these was published during the war years in the Doklades (Treatises) of the USSR and in the Mathematics’ Collection. Another portion remained in the manuscripts (twelve papers and several letters). Still, it is quite possible Shmulian had no time to reflect in these journals all his ideas and intentions.

Considering the military and wartime mathematical achievements of the Vitold Shmulian, one should be aware that they happened in the context of tremendous losses and stresses in his family. Just a little over three years before his voluntary enlistment, in January 1938, Vitold’s father, then a well-known attorney and law lecturer in Odessa, was arrested by the NKVD (an organization that at that time combined the functions of the regular and secret police) on fabricated charges during the worst period of Joseph Stalin’s Great Terror. Lev Shmulian was sentenced to six years of hard labor in the remote northern camps of the Gulag. It was also customary to arrest members of the families of the victims of Stalin’s terror, who were called enemies of the people. Upon Lev’s recommendation, his wife, Isabella, and daughter, Alla, clandestinely left Odessa in late June of 1938 for Taganrog, where Theodore was already living. By the fall of that year, Alla managed to pass the entrance exams and join the Rostov Medical Institute, thus overcoming the likely odds of being rejected as the daughter of an enemy of the people. She worked as a nurse at an evacuation hospital in the USSR during the war. Theodore valiantly served in a sapper detachment of the Red Army during the last two years of the war.

As part of Operation Barbarossa, nations aligned with Nazi Germany also took part in the invasion. Romanian troops occupied Odessa beginning in October 1941. Vitold’s wife, Vera Gantmacher, who herself was an established mathematician with whom Vitold had several papers published, was trapped in the city because she refused to flee and leave her elderly parents behind. All three were executed in a ghetto near Odessa in March 1942 by the Romanian fascists. Vera’s brother, Felix Gantmacher (1908-1964), miraculously escaped the perilous situation of his family and after the war became one of the leading Soviet experts in ballistic rocket mechanics.

During his military service, Vitold Shmulian corresponded regularly with his former mathematics’ professor M.G. Krein [3,4], which helps us to understand his character. In the summer of 1942, Shmulian wrote, “I am writing this letter at the top of the church. Here I conduct an observation of a disposition of the German troops. In the morning I was at another observation position and also was involved in the detection of the coordinates of the targets…”

The letter ended unconventionally.

“I will send you soon a letter reporting on my latest research.”

It is evident Shmulian meant the results of mathematical research he worked on continuously, even at the front during periods of relative calm.

On June 16, 1943, during a radio transmission about the scientists serving at the front, one of the 20th century’s most eminent mathematicians Andrey N. Kolmogorov highlighted the uninterrupted scientific activity of Shmulian.

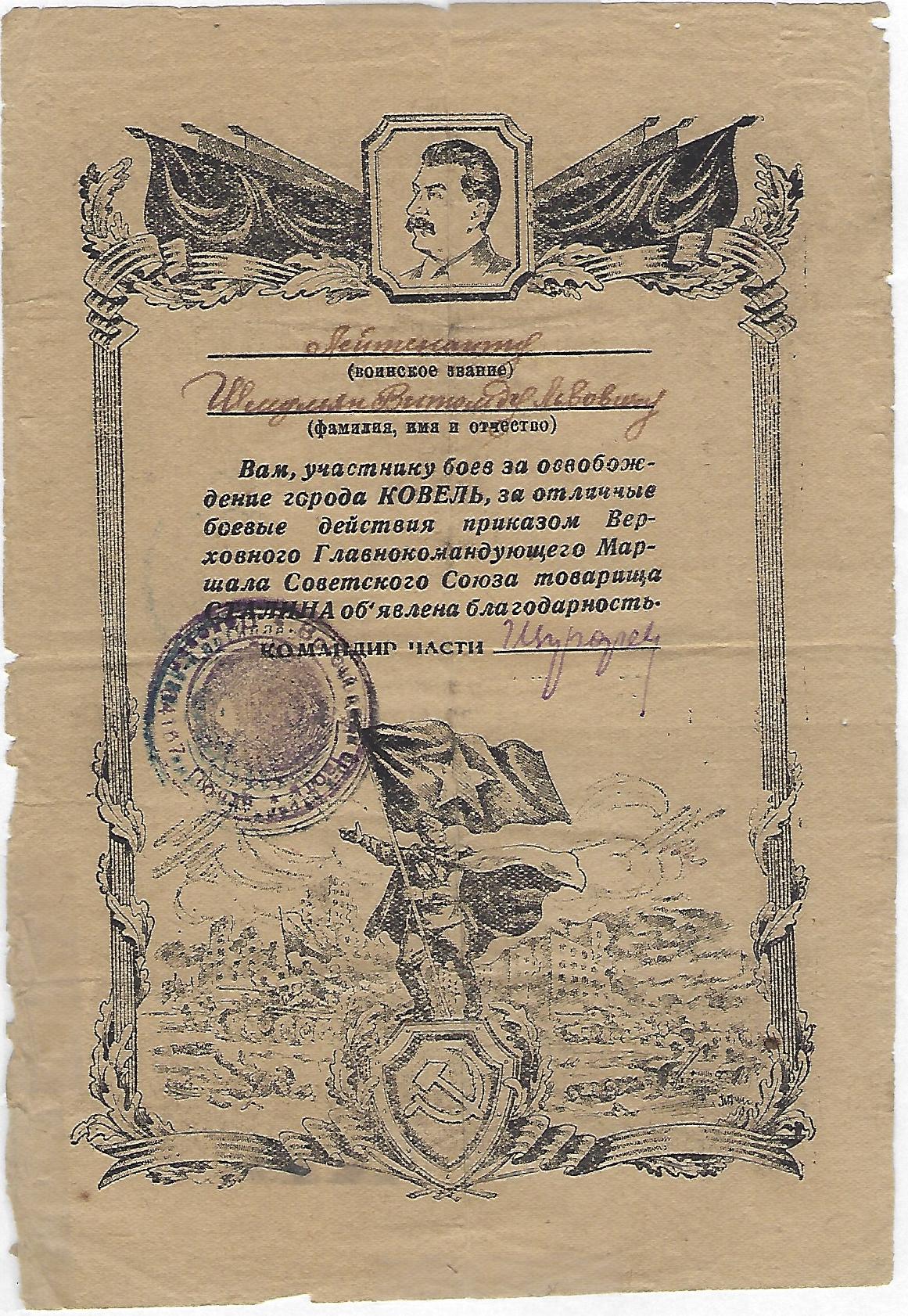

In the battles for the city of Sevsk in 1943, Shmulian was awarded a medal for bravery, and in 1944, for his participation in an operation in Kovel, he received the Order of the Great Patriotic War. In the papers accompanying the awards, it was reported that “despite the fire and bombing from the enemy aircraft, Lieutenant Shmulian has always timely located the targets.” Again, “During the battles for Kovel started on July 7, Lieutenant Shmulian enabled a precision setting of the firepower systems of the artillery regiment. Based on his data, there were two anti-tank guns and seven machine guns eliminated one observation position and two bunkers destroyed, and fire from two mortar batteries of the enemy was suppressed.”

From the letters Shmulian wrote from the front and from the memories of his regimental colleague Colonel G. P. Tarasov, whom the author met in the mid-1960s, emerges a vibrant image of a patriot and warrior-mathematician. A boundless thirst for knowledge that always distinguished him grew even deeper and more profound while he was in the army. Before the army, his passion for mathematics had always given the impression he was a person who stayed far from the realities of life.

Meanwhile artillerist Shmulian, after becoming a commander of the artillery’ reconnaissance team very soon won the confidence of his superiors and his charges. He studied special geodetic literature (geodesy is the science of accurately measuring and understanding the Earth’s geometric shape). His letters from the front show multiple requests for more new literature in that field, and he put all topological reconnaissance on a serious scientific footing. As an officer and mentor, he also taught his charges that discipline. At the front, he gave lectures on probability theory to his fellow officers. Shmulian introduced, and his superiors accepted, a number of valuable ideas related to camouflage, setting false fire positions, etc.

[adinserter block=”10″][adinserter block=”11″]Throughout a considerable mail exchange that Shmulian conducted with his friends, relatives, and colleagues, he always reminded them what a joy the books delivered to him on the front gave him and what a hunger he had for them. He reread all the works of Turgenev, the novels of Chekhov and Gorky, and the poems of Lermontov and Nekrasov. Although he was proficient in reading German and English scientific literature, he thoroughly studied a self-tutoring book on French, which serendipitously came into his hands. Nevertheless, he always retained a passion for mathematics.

M.G. Krein wrote [3,4], “In the letters to me, V. L. Shmulian kept asking about new results from his colleagues and requested I send him new books on mathematics. In the spring of 1942, I sent him a recently published book, authored by me and F. R. Gantmacher, The Oscillating Matrices and Small Oscillations of the Mechanical Systems. It is doubtful Shmulian would have spent time on a book so far removed from his scientific interests in peacetime, but we later found out he studied it in detail. Moreover, he sent a long list of necessary corrections and improvements that were utilized in the second edition of that book in 1950.”

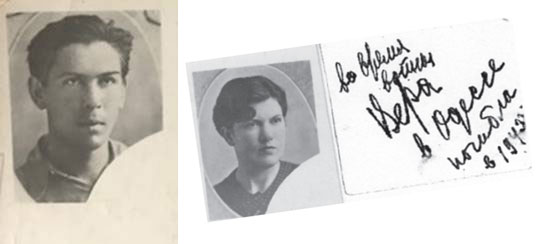

In a photograph from the front, the face of a young man filled with vigor and twinkling eyes looks at us. There are no doubts, however, he understood the enormity of the ongoing historical battle and considered he might not be able “to have the opportunity to continue his mathematical work…One would have desired that somebody continue these studies. It would be pitiful if my undertakings were stopped in their tracks.”

On August 29, 1944, he would have turned thirty, but a few days earlier, Senior Lieutenant Vitold Shmulian fell heroically and was buried in a common grave in Praga, a Warsaw suburb. A year later, his father Lev would die while still serving his sentence in the Gulag. His mother, Isabella, survived the war and the loss of a husband and a son to different evils, passing away in 1975. His brother Theodore survived the war and became an engineer of high-pressure vessels. He passed away in 1998, but is still remembered as a master and a leading figure in the game of Russian checkers. After the war, his sister Alla became a reputable x-ray doctor, eventually moving to the U.S. with her family, including her son, the author of this article. She passed away in Pittsburgh in 2010.

[adinserter block=”13″][adinserter block=”16″]Kolmogorov would present Vitold’s final mathematical work for posthumous publication. One of the scientists who knew Shmulian stated, “With his works on the topology of the linear spaces, carried out in the 1940s, Vitold Shmulian was ahead of his time by some 20 years; perhaps, the war plucked away from the world a new Lobachevski or Einstein.” Shmulian’s work, some of which immediately assumed the status of mathematical classics, did not get lost but found new life in the works of the contemporary mathematicians and are taught in university courses [5-8].

Although the final number is still being debated and may never be accurately determined, the Soviet Union had the greatest number of military deaths during World War II. In Western media, these soldiers are usually depicted as intense ideologues or naïve lambs being led to slaughter. However, as in any conflict, each was an individual with hope and dreams for the future. Vitold Shmulian’s passion and life’s work did not stop until his life was literally taken from him. Although he perished on the battlefield, his work continues to benefit the generations of mathematicians that have come after him.

1 Following the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, Lwów came under the control of the Soviet Union for almost two years. Banach, from 1939 a corresponding member of the Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, and on good terms with Soviet mathematicians, had to promise to learn Ukrainian to be allowed to keep his chair and continue his academic activities. Following the German takeover of Lwów in 1941 during Operation Barbarossa, all universities were closed and Banach, along with many colleagues and his son was employed as lice feeder at Professor Rudolf Weigl‘s Typhus Research Institute. Employment in Weigl’s Institute provided many unemployed universities professors and their associates’ protection from random arrest and deportation to Nazi concentration camps.

Sources

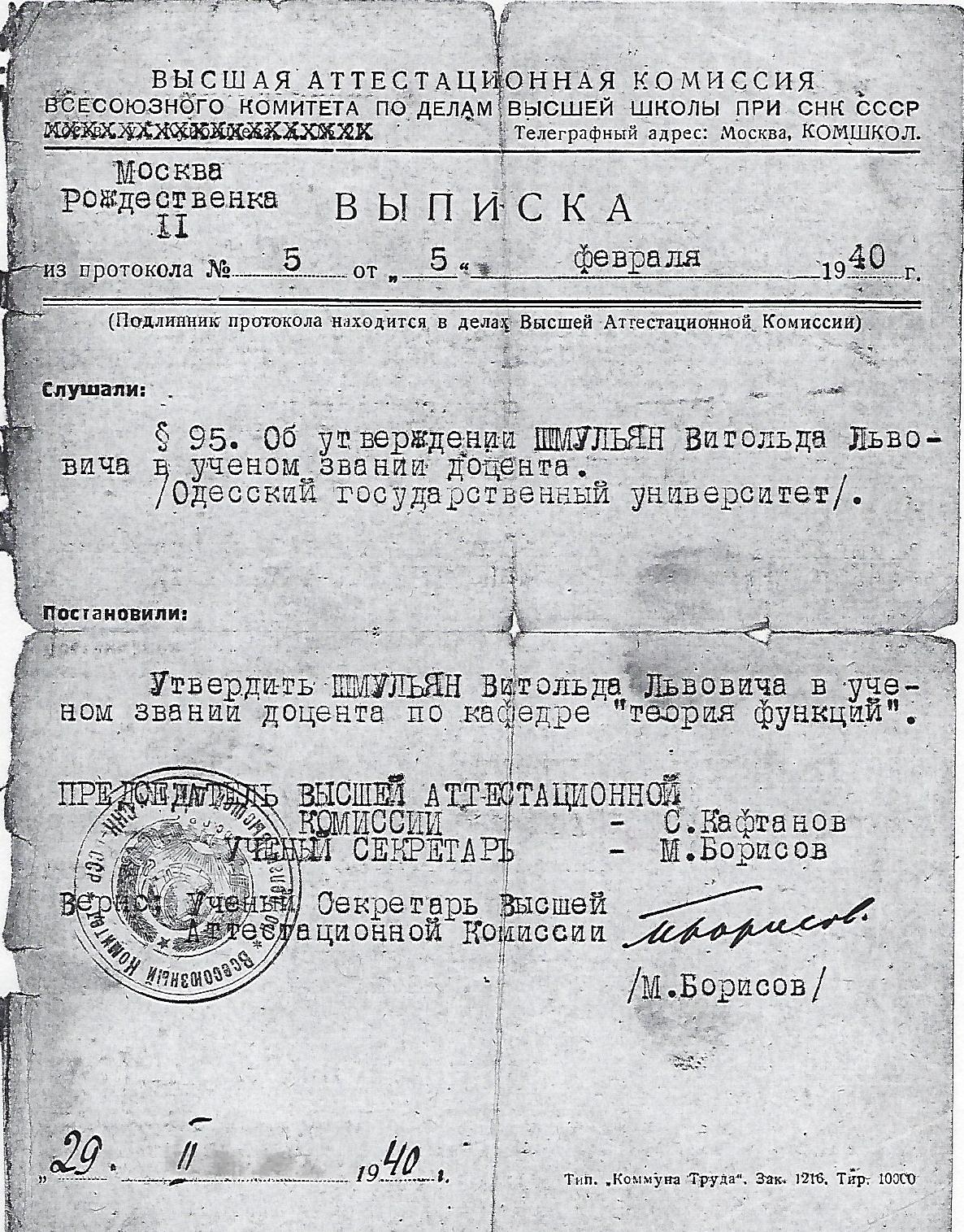

A certificate-confirming acceptance of Vitold Shmulian as a docent (professor’s assistant) at the chair of the Theory of functions of the Odessa State University, February 29, 1940.

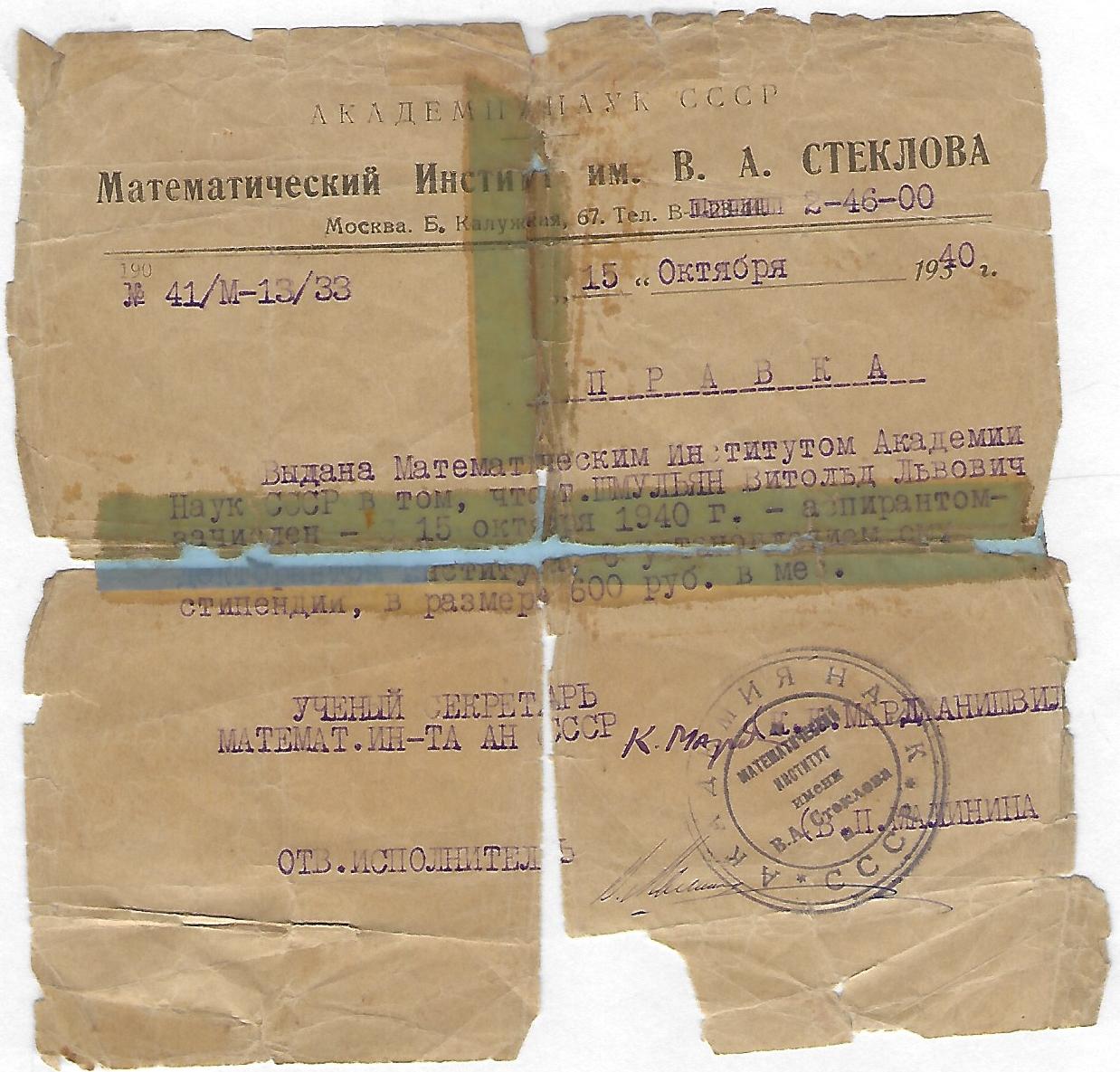

A certificate-confirming acceptance of Vitold Shmulian (Шмульян Витольд Львович) as a post-doctoral student of the Steklov Mathematics Institute at the USSR Academy of Sciences.

Moscow, USSR, October 15, 1940.

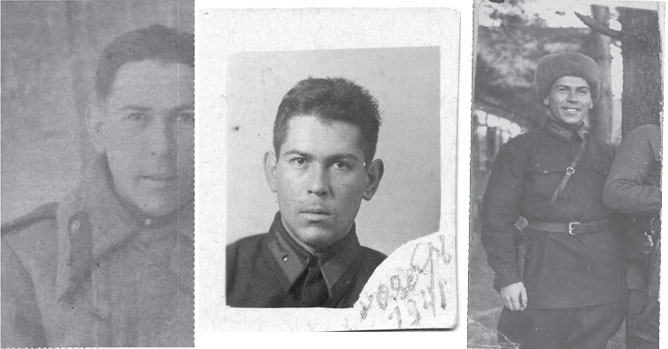

Vitold Shmulian promoted to the rank of officer in November of 1941.

His last rank (in 1944) was senior lieutenant.

A certificate of appreciation for his combat successes. It reads, “To Lieutenant Vitold Lvovich Shmulian. To you, the participant of the battles for the liberation of the city of Kovel, for excellent fighting operations, an appreciation is announced by the Supreme Commander Marshal of the Soviet Union comrade Stalin. Signed: Commander of the detachment (signature). 1944.

A Soviet postage stamp of1944. It depicts the Order of the Patriotic War. It was one of the military awards to Vitold Shmulian for the successes on the battlefield.

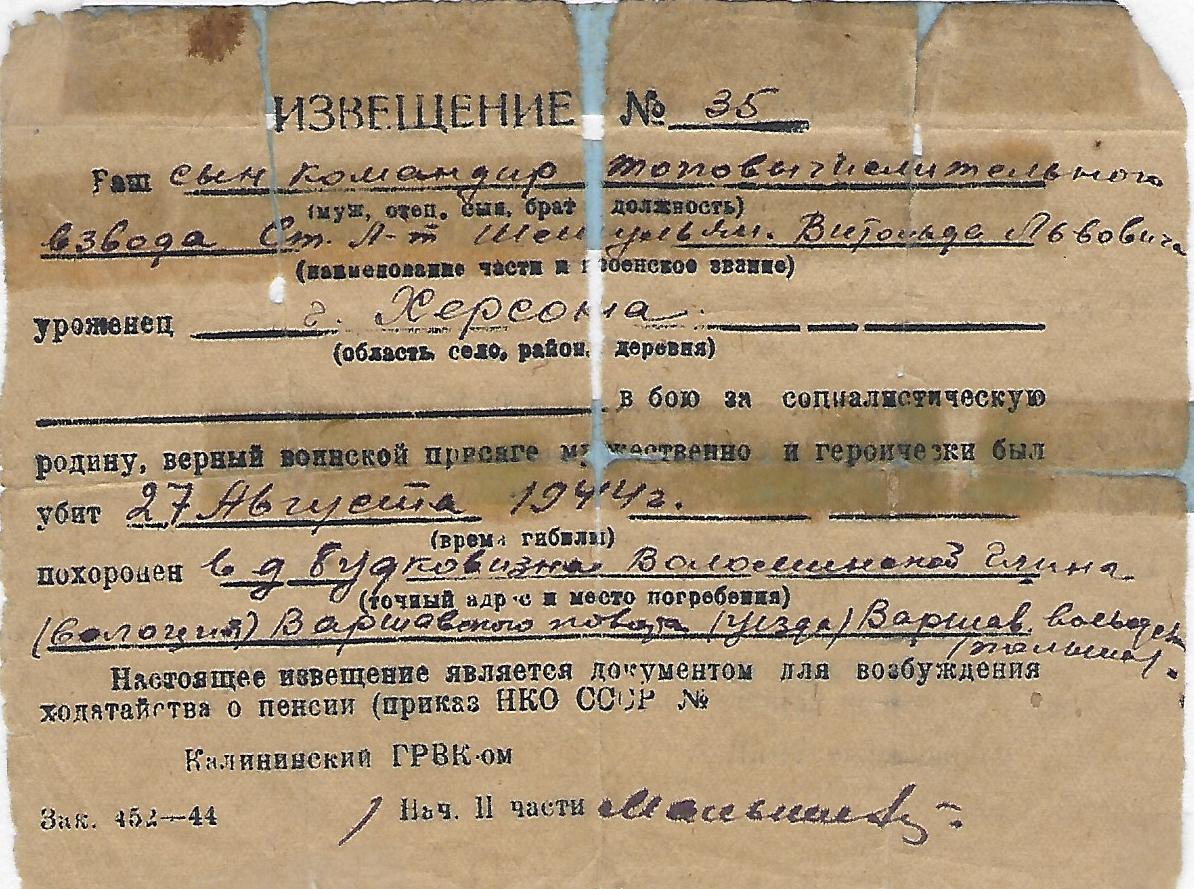

The notice of death of V. Shmulian to his mother.

It reads, “Notification #35. Your son, the commander of a reconnaissance team, Sr. Lieutenant Shmulyan Vitold Lvovich, born in the city of Kherson, in the fight for the socialistic motherland, faithful to the military oath, was courageously and heroically killed on August 27, 1944. He was buried in the village Budkovizna of Voloshinskaja Glina (Voloshia), Warsaw District, Poland. This notification is a basis to apply for a pension (by the order of NKO, Peoples’ Commissar of Defense, of the USSR, #). Kalinin’s GRVK (District’ Military Commissariat). Signed: Chief of II Department, Malyshev.

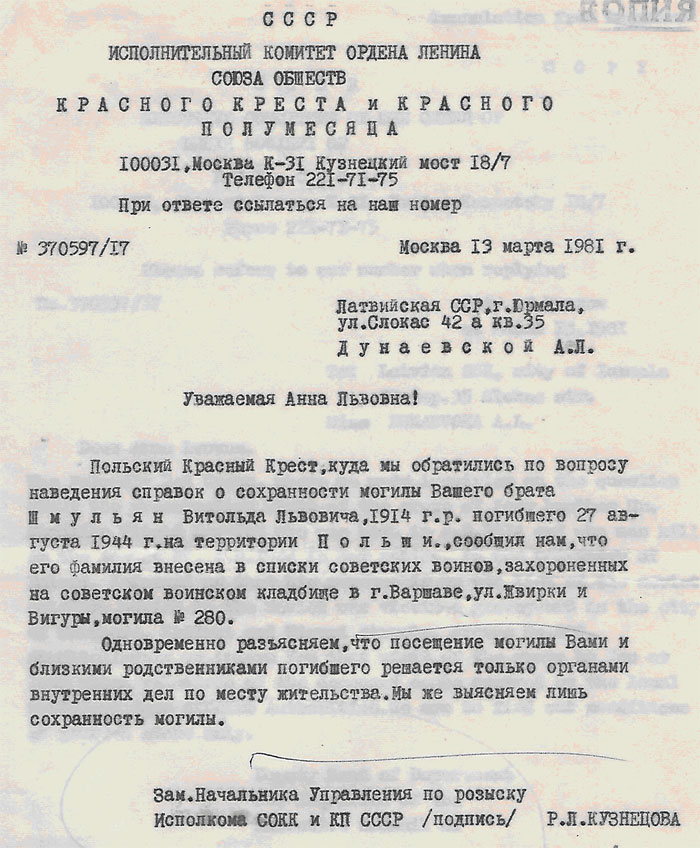

A statement of the USSR’s Red Cross reads, “The Polish Red Cross states that the name of Vitold Shmulian, who was killed in the territory of Poland on August 27, 1944, is retained in the list of the Soviet soldiers buried in the Soviet military cemetery in Warsaw, Zhvirki Str., grave site # 280.”

Vera Gantmacher, wife of Vitold Shmulian, and a mathematician herself, who was executed with her parents in a ghetto near Odessa in 1942.

Right: a note from Isabella (Vitold’s mother) on the backside of the photograph.

It reads: “During the war, Vera perished in Odessa in 1942.”

Vitold’s sister Alla Dunayevskaya (nee Shmulian) in the nurse uniform at the evacuation hospital (circa 1942).

A list of important works of Vitold Shmulian (1937-1944). The entries are given in Russian, Ukrainian, French, and English.

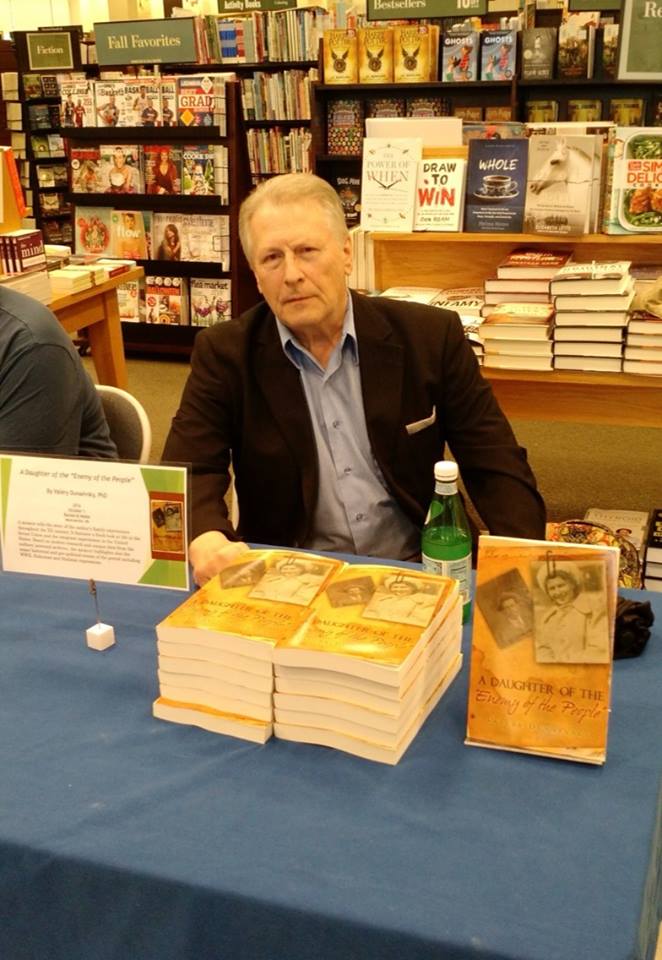

The author, Valery Dunaevsky, at the sale of his book, “A daughter of the ‘Enemy of the People,’” dedicated to the family of Vitold Shmulian.

Valery Dunaevsky received his Ph.D.in mechanical engineering in Riga, Latvia. During his professional carrier in the former USSR and later, since 1979, in the USA, he became the acclaimed author of many technical papers and patents. His research has been effectively used in the development of engines, compressors, and brakes. He continues to be a reviewer in the field of lubrication and tribology for several international publications. He is author of the biographical/autobiographical memoir “A Daughter of the ‘Enemy of the People’” about the life in the USSR during the 1930s-1970s, and the immigrant experiences in the USA. He is also the author of a number of the articles in several online periodicals addressing the anger of the day. He can be reached at valvic833@gmail.com.

Учёный, публицист, автор и соавтор нескольких книг Валерий Дунаевский (Valéry Dunaévsky), PhD, специалист в области прикладной механики, увлекающийся также литературным творчеством и журналистикой

Эта рассылка с самыми интересными материалами с нашего сайта. Она приходит к вам на e-mail каждый день по утрам.